Making Noise About Silent Film Series Lecture #1

African American Representation in Silent Film

D.W. Griffith and the Birth of Defamation

by Dr. Barbara Tepa Lupack

Delivered Wednesday, February 23, 2022, at the Rossell Hope Robbins Library at the University of Rochester

This initial lecture in the Making Noise About Silent Film: Conversations about Cinema, Culture & Social Change Lecture Series draws on ideas first explored by Dr. Barbara Tepa Lupack in Literary Adaptations in Black American Cinema: From Micheaux to Morrison (University of Rochester Press, 2002); the expanded edition, Literary Adaptations in Black American Cinema (University of Rochester Press, 2010); and various essays, including “Uncle Tom and American Popular Culture: Adapting Stowe‘s Novel to Film,” in Barbara Tepa Lupack, ed., Nineteenth Century Women at the Movies (Bowling Green: Popular Press, 1999). It also builds on Lupack’s work as Humanities New York Public Scholar (2015-2018).

The Origin of the Uncle Tom Figure

Edwin S. Porter’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Edison, 1903) introduced “Uncle Tom,” the character most immediately associated today with black servility and subservience, into cinema culture. Tom had first appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel of protest against the passage in 1850 of the Fugitive Slave Act that enforced the return of escaped slaves to their owners. An exemplary figure whose saintliness aroused the wrath of the wicked slave trader Simon Legree, Stowe’s Tom inspired the love of Little Eva and the admiration of Eva’s father Augustine St. Clare, of his fellow slaves, and of the novel’s many readers.

With Uncle Tom at her bedside, Little Eva ascends into heaven in Edwin S. Porter’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903). (Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archive.)Film Versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Porter’s film, told in fourteen tableaux modeled on the tableaux vivants popularized by French film artist Georges Méliès, featured key scenes such as the death of Eva. But it recast the story to suggest a link between Tom’s treatment and national reunification following emancipation, thus allowing audiences to enjoy the cinematic imagery without having to contemplate the underlying evils of slavery. In the silent era alone, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was retold and reworked numerous times, by, among others, Lubin Company (1903), Thanhouser and Vitagraph (1910), Kalem and Universal-Imp (1913), World Film Company (1914), Famous–Players-Lasky (later Paramount; 1918), and Universal Pictures (1927). The story was further distorted in such crude take-offs as Topsy and Eva (1927), in which the Duncan Sisters brought the offensive representations from their popular blackface minstrel act to the screen.

The Duncan Sisters brought their vulgar vaudeville routine to the screen in Topsy and Eva (1927), one of many silent versions of the Uncle Tom story. (Courtesy of the Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.)CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACIAL STEREOTYPES

>>What Black stereotypes can you identify in today’s films and television shows? How do they shape popular perceptions?<<

Stereotyping in The Birth of a Nation

It was a different film, though—D. W. Griffith’s venomous and controversial The Birth of a Nation (1915)—that popularized the character of the villainous, sexually aggressive Black and various other racist stereotypes (including the devoted Mammy willing to risk her own life to protect her master’s family and property) that would be imitated by filmmakers for years to come.

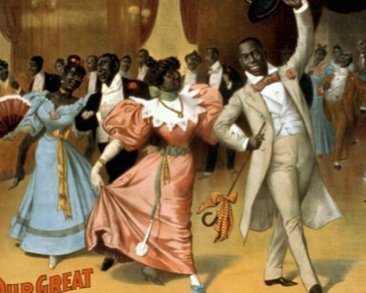

Many of those pejorative images had originated in the plantation literature and ubiquitous minstrel shows, stage productions, and “Tom shows” during the last half of the nineteenth century. Yet, even though those stereotypes were not original to him, Griffith reinforced them and ensured that they took root in the American imagination and in the culture.

Uncle Tom minstrel shows were a popular entertainment in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACIAL STEREOTYPES

>>Is there value in watching films such as The Birth of a Nation today? Or should films as inherently racist as Griffith’s Birth be banned from curricula and from exhibition? If not, what purpose do such films serve?<<

The Birth of a Nation’s Racist Underpinnings

Both a masterpiece of filmmaking and an example of the most virulent racism, Griffith’s film was based largely on The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905), the second in a trilogy of novels by former Southern Baptist minister Thomas Dixon and on a dramatization of the novel that was produced soon afterward. [1]

Retrogressive and racist, Dixon was as romantic in his glorification of the Old South as he was vicious in his depiction of Black Americans, and he used his works—all of which were notorious for their attacks on liberal ideological movements like integration, feminism, and pacifism—as an attempt to counter the anti-slavery sentiments of Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Reportedly, his inspiration for The Clansman came in 1901 at a performance of a Tom play. Infuriated by what he saw as the injustice of the play’s attitude toward the South, he vowed to tell what he considered to be the “true story” of American history, from the glory of the antebellum South to the evils of miscegenation and postwar Reconstruction and finally to the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan, an order of contemporary knights whose holy quest, in Dixon’s view, was the restoration of the American way of life (or rather Dixon’s idea of the American way of life). At the opening of a stage version of his novel in 1906, Dixon spoke at the intermission about his hopes and intentions:

“My object is to teach the north, the young north, what it has never known—the awful suffering of the white man during the dreadful reconstruction period. I believe that Almighty God anointed the white men of the south by their suffering during that time . . . to demonstrate to the world that the white man must and shall be supreme.” [2]

Griffith’s Racist Ideology

The panoramic sweep of The Clansman certainly appealed to Griffith, whose own vision was as epic and whose perspectives on history were as sentimentalized as Dixon’s. Born a child of the Confederacy in Kentucky in 1875, Griffith was steeped in an atmosphere of racial intolerance. Keenly sensitive to the South—its travails, its burden of race, its rural inferiority—and full of reverence for its heroes, among whom were numbered some of Griffith’s own forebears (including his father, “Roaring Jake” Griffith, a Confederate veteran), he displayed a “unique mind-set [that] made him the most credible interpreter of Southern and Black experience on film, at least to a generation wanting relief from the clatter of urban change, with the result that the new Negro of the cities was drowned in the martial vision of Griffith’s Southland.” [3]

Not only in short pictures such as His Trust and His Trust Fulfilled but also in the scores of other Civil War melodramas like In Old Kentucky and The Battle that he produced for Biograph and released between 1909 and 1911, Griffith promoted his racist attitudes about “faithful” and “right-thinking Negroes”—attitudes that most Southerners shared and that many Northerners and Middle Westerners casually accepted.

In short pictures such as His Trust and His Trust Fulfilled (1911), Griffith promoted his racist notion of “right-thinking Negroes” such as the self-sacrificing old servant played by Wilfred Lucas (in blackface) who, after his Confederate master’s death, remains “faithful to his trust.” (His Trust, Biograph, 1911)As long as Blacks stayed loyal to their families and their land, Griffith’s films seemed to say, all was right with the world; their mistreatment, impoverishment, or other sacrifices were inconsequential.

Origins of The Birth of a Nation

It was Biograph writer and scenarist Frank Woods who arranged a meeting with Griffith, Dixon, and several possible backers for the film, after which the director and the novelist struck a deal that included not only the purchase of the idea and royalties on the production but also the promise of collaboration in the actual filmmaking. Soon after the Christmas holidays of 1913, Griffith and Dixon left for the West Coast, whose atmosphere, film scholar Thomas Cripps suggests, reinforced their traditional Southern values. Remote from urban life, the two romanticized the Old South; cast several actual Southerners (like Henry B. Walthall, who played Ben Cameron, and Lillian Gish, Griffith’s favorite actress at the time, who played Elsie Stoneman) in key roles; and even replicated Dixie to the extent of segregating the barracks of the Black extras, most of whom were Californians so grateful to have work that they did not complain (SFB 45). According to Karl Brown, Griffith’s assistant camera operator, the director also instructed the carpenters to build the street set in such a way as to re-create the familiar and crucial architecture of the popular “Tom shows” that had amused and entertained white audiences for decades. [4]

Director D. W. Griffith, at his desk and on location with his crew. (Courtesy of the Billy Rose Theatre Division, the New York Public Library.)Premiere of The Birth of a Nation

As the rising cost of the production forced Griffith to continue raising capital throughout the summer and into the fall of 1914, several adaptations were prepared, including one based on Dixon’s unsuccessful dramatization of his novel and written for Dixon by Frank Woods (eventually billed as Griffith’s co-scenarist on the project). Yet Griffith is said to have worked largely without a written script. Rehearsed for six weeks, filmed in nine weeks, and edited for three months,[5] the film previewed under the title The Clansman in California early in 1915 and premiered under its new title The Birth of a Nation a few weeks later in New York. In an age during which most films were crude shorts made on small budgets, Griffith’s $100,000 spectacle was a polished, well-edited, and well-lit masterwork with an unprecedented running time of three hours (twelve reels). After a private screening of the film in the White House,[6] President Woodrow Wilson, one of Dixon’s former classmates at Johns Hopkins, reportedly compared it to “writing history with lightning” and regretted “that it is all so horribly true.”[7]

Announcement for a screening of The Birth of a Nation (1915) and one of the many posters advertising the film. (Announcement courtesy of the Library of Congress.)A Poisonously Racist Story

Contrary to Wilson’s pronouncement (which Wilson later disavowed), The Birth of a Nation was not horribly true; but it was remarkable in other ways.

Griffith, a bigot in his politics, proved to be a technical genius in his filmmaking. Utilizing numerous innovations such as cross-cutting, close-up and fade-out shots, effect lighting, iris shots, and split screens, he was able to create stunning images and sequences like the battle scenes and chases.

Most surprising, perhaps, was Griffith’s reworking of Dixon’s novel into a compelling (although still poisonously racist) story of the Cameron family, who—along with their happy and devoted slaves—lead an idyllic existence in Piedmont, South Carolina. That existence, of course, is shattered by the Civil War.

Terrorized by “Negro raiders” during the war, the Cameron family must deal with even more horrors during Reconstruction, as carpetbaggers and Northern Blacks move into the area and exploit the Southern former slaves by unleashing their bestial natures and turning them into renegades. Under the new “Negro rulership,” Blacks begin subverting the whole social order: they push whites off the walkways, steal their property, keep them from the ballot boxes, turn a legislative session into an occasion for chicken-eating and whiskey-chugging rather than governance, and—worst of all, in the film’s view—assault white women and attempt to intermarry.

Meanwhile, the Northern Senator Austin Stoneman, patriarch of the Pennsylvania Stonemans whose lives have become intertwined with the Camerons, insists on pushing for the equal rights of Black citizens. [8] After first dispatching his mulatto protégé Silas Lynch “to aid the carpetbaggers in organizing and wielding the power of the Negro vote” (according to the title card), Stoneman travels to Piedmont and sees for himself the damage that has been wrought.

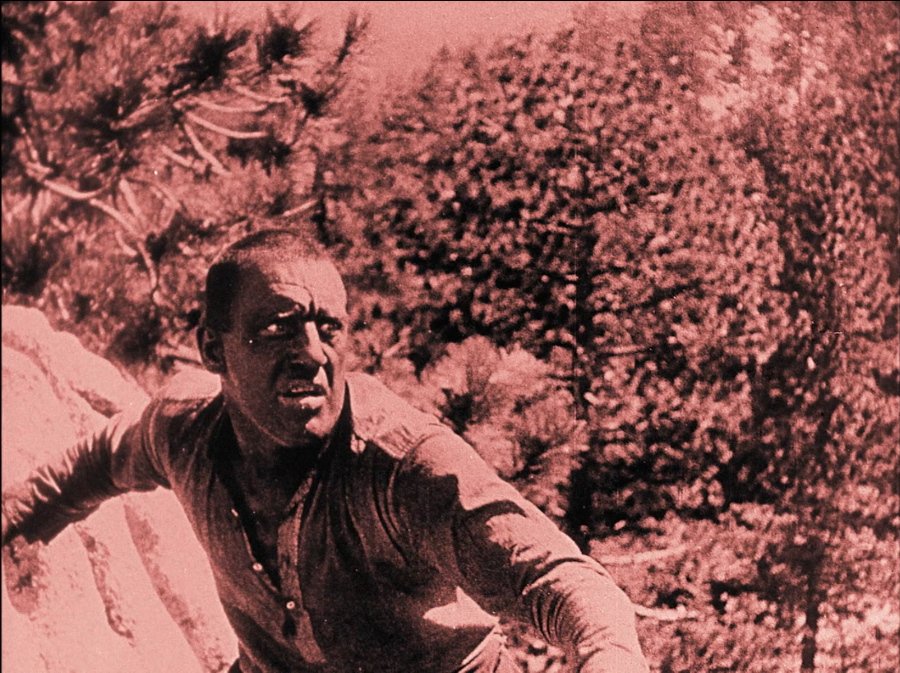

As Blacks continue to terrorize whites, even Gus (Walter Long), a former Cameron family slave, becomes “the product of the vicious doctrine spread by carpetbaggers.” In a harrowing seven-minute sequence, Gus pursues the Camerons’ daughter Flora (Mae Marsh) through the woods until she jumps to her death into a ravine to escape his lecherous advances. [9]

One of the most shocking scenes in The Birth of a Nation was the death of Flora (Mae Marsh), who jumps from a cliff to escape the advances of Gus (Walter Long). (The Birth of a Nation, 1915)Then Lynch (played by white actor George Seigmann in dark theatrical makeup to heighten the effect of his blackness, which Griffith equated with savagery) presumes to marry Elsie Stoneman, portrayed by the light-haired, pale-skinned Lillian Gish. [10] When Elsie refuses, he binds and gags her in order to enact a “forced marriage.”

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACIAL STEREOTYPES

>>Is it possible to analyze and discuss a film such as The Birth of a Nation purely from the perspective of its innovative filmmaking techniques? If so, how can the medium be separated from the message?<<

Racist Plot Elements in The Birth of a Nation

The social chaos created by arrogant and aggressive Blacks in The Birth of a Nation leads the disenfranchised Southerners to form the Ku Klux Klan, who begin their nights of terror by capturing, castrating (a scene excised from most versions), and murdering Gus and depositing his corpse on the mulatto Lynch’s doorstep. [11]

After learning of Lynch’s intention to marry his daughter, Stoneman finally recognizes the error of his views on racial equality (which the film attributes to the wiles of his mulatta mistress and housekeeper Lydia Brown, whom Griffith calls the “weakness that is to blight a nation”).

Griffith placed blame for Stoneman’s “dangerous” opinions about racial equity on his mulatta mistress Lydia Brown. (The Birth of Nation, 1915)Naturally, Ben Cameron and his fellow Klansmen rescue Elsie in time to thwart Lynch’s evil plans and to save Dr. Cameron and his family from the renegade Blacks who have surrounded the cabin where they are hiding; and, in a symbolic new union of opposing sides, Ben and Elsie join Phil and Margaret Cameron on a double honeymoon.

With the white Southerners again in command and the Blacks obediently under control, the world is set aright—a conclusion reinforced by Griffith’s final original allegorical shot, of Christ ascending into Heaven after having vanquished the God of War.

“With immediacy and intensity, Blacks decried The Birth of a Nation as sheer propaganda for the Ku Klux Klan, who actually used it as an organizing and recruiting tool; and they argued—correctly—that the film’s sympathetic portrayal of mob violence as a kind of divine retribution would lead to more lynchings.”

— Dr. Barbara Tepa Lupack

Black Audience Response

If the film was like history written by lightning, then the Black response could only be analogized as thunderous.

With immediacy and intensity, Blacks decried The Birth of a Nation as sheer propaganda for the Ku Klux Klan, who actually used it as an organizing and recruiting tool; [12] and they argued—correctly—that the film’s sympathetic portrayal of mob violence as a kind of divine retribution would lead to more lynchings. [13] (The Klan itself had been revived and reinvigorated in 1915 by Joseph Simmons, an ex-minister “inspired” by the film. As Terry Ramsaye observed, “The picture . . . and the K.K.K. secret society, which was the afterbirth of a nation, were sprouted from the same root.” [14]

The NAACP, formed a few years earlier in 1909, picketed the New York premiere; branches of that organization in other cities led large demonstrations against the film’s showings.

Members of the NAACP picket outside the Republic Theatre in New York City to protest the screening of the movie The Birth of a Nation. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)Some of those demonstrations were minimally effective: in Boston, for example, Mayor James Curley—in an effort to keep Black votes—agreed to small cuts before the film was screened. Yet he defended the film and argued that its characterizations were no more grotesque than Shakespeare’s. A few Black protesters in Boston managed to get by the two hundred police officers stationed outside the Tremont, a segregated theater: inside, they egged the screen and threw a stink bomb into the crowd. Outside, brawls erupted. [15]

Increasing Criticism

Religious and civic groups joined the various protests nationwide, and a number of newspaper editorials came out strongly against the picture’s racism. White reviewer Jane Addams wrote caustically that the movie misused history and that Griffith gathered “the most vicious and grotesque individuals he could find among the colored people” and then tried to show them “as representatives of the . . . entire race” (SFB 58).

The Black press, even more direct in its attacks, used the film as a vehicle to promote Black self-determination and to encourage filmmakers to provide more complimentary and realistic representations of Black life in their productions. James Weldon Johnson, for instance, charged in the New York Age (April 15, 1915), “Not in this whole picture, which is supposed to represent the birth and growth of the nation, is there one single Negro who is both intelligent and decent.” [16] New York Age publisher Lester Walton, angry that Griffith had managed to create the perception that Blacks were not “true” Americans, demanded action. Hinting darkly that the matter would be regarded differently had it been the Jews or the Irish who were so badly maligned, Walton concluded that “the photoplay is vicious, untrue, unjust, and had been primarily produced to cause friction in Northern cities” (SFB 58). As The Crisis editor W. E. B. Du Bois reported, while the backlash may have failed “to kill The Birth of a Nation, [at least] it succeeded in wounding it” (Gaines, FD 230).

Griffith’s Response to the Criticism

Griffith professed shock at Blacks’ resentment of his work and, somewhat disingenuously, pointed to one of the opening titles that explicitly stated the film did not reflect on “any race or people.” He added that “[saying I am racist] is like saying I am against children, as they [Negroes] were our children, whom we loved and cared for all our lives.” [17]

Famously, he offered to contribute $10,000 to charity if Moorfield Storey, the white head of the Boston branch of the NAACP, could find a single example of historical inaccuracy in the film—an offer Storey declined because he refused to view the film. And until his death in the late 1940s, Griffith continued to maintain that Birth of a Nation was not a racial attack. [18]

Dixon, on the other hand, countered the criticism of his part in the controversial motion picture by saying that he did not hate Blacks, just the mixing of Black blood with white, and suggested that even Abraham Lincoln would have admired his position.

Commercial Success

Mulatto lieutenant-governor Silas Lynch tries to coerce Elsie Stoneman (Lillian Gish) into a “forced marriage.” (The Birth of a Nation, 1915)Despite the controversy, which continued for years with each proposed or scheduled revival of the film, The Birth of a Nation was a tremendous commercial success. Even at the steep ticket prices that Griffith charged, the film found a large and receptive audience. [19] As Wil Haygood noted, more than twenty-five million people, “a quarter of the population, . . . eventually saw the film during its initial run,” during which “the movie grossed between fifty and sixty million dollars.” [20] And precisely for that reason—the enormity of Griffith’s audience and the ease with which they accepted his racial cant—Griffith was able to shape the way that Blacks would be portrayed in American films for years to come.

From the selfless Tom and devoted Mammy to the happy pickaninnies, The Birth of a Nation fixed many stereotypes in the popular mind and culture.

Probably, though, the ugliest and most damning was that of the brutal Black, or the Black “buck.” A far cry from the complacent and grateful slave of cinema lore, he was unlike anything ever seen before on screen. Oversexed and barbaric to the point of being subhuman, the buck lacked all sense of conscience. In Griffith’s film he expressed his rage through his frequent physical assaults—on white men, even on the Camerons’ Black slave and other loyal Black family retainers.

But, for most white viewers, his most frightening characteristic was a lust for white women, which whipped him into a frenzy and led to his most heinous attacks. For those white viewers, Gus’s pursuit of Flora, which results in her suicide, and Lynch’s coercion and literal bondage of Elsie simply illustrated the hideous extreme of the rapacious buck’s behavior. (By comparison, as Michele Wallace observed, in an earlier scene, an ordinary white Union soldier stares longingly at Elsie but does not dare to speak to her. “The inference is that the good man of superior race holds his tongue and settles for unrequited passion whereas the man of inferior race has no control over his passions.”) [21]

Intertwining of Racism and Sex

It is through these two characters of Gus and Lynch, “one always panting and salivating, the other forever stiffening his body as if the mere presence of a white woman in the same room could bring him to a climax,” Donald Bogle writes, that Griffith revealed the tie between sex and racism in America. [22] By playing on “the myth of the Negro’s high-powered sexuality” and then articulating the great white fear that every Black man longs for a white woman, both because she is desirable and because she symbolizes “white pride, power, and beauty” (TCMMB 13-14), Griffith portrayed the Black man as innately animalistic and psychopathic.

Fear of rampant Black sexuality, after all, was—as Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence demonstrate—a cornerstone of white supremacist ideology, and the image of the Black male as savage brute who wanted only to violate the sanctity of Southern womanhood became a “powerful weapon used by white men to reassert control over Black labor in the post-slavery age.” [23]

To reinforce that negative perception, Griffith repeatedly used caricature and exaggeration to emphasize the physical ugliness of his Black characters and what he perceived to be the repugnant, animalistic features of their bodies: their flat feet, their yellow eyes, their large noses and mouths, their inability to stand up straight. [24] Worst of all, knowing that such a bestial screen type could arouse only hatred, Griffith exploited it at every opportunity in his film. [25]

Proliferation of Racist Stereotypes

The image of the hulking and lusting Black buck was thus indelibly etched. [26] Yet, unlike the subservient Tom or the “faithful soul”—that is, the acquiescent Black who knew and kept his place in The Birth of a Nation and Griffith’s other pictures—the buck did not become ubiquitous because that image ran counter to the enduring plantation myth of contented Blacks as well as to the Southern thinking that rationalized slavery because it was in the best interests of the Blacks who were enslaved.

While the buck was occasionally featured in early films like Broken Chains (1916), most studios remained mindful of the controversy over Griffith’s production and refrained from depicting so hostile and explosive a character. Free and Equal (1915), for instance, the only picture of the period to approach Griffith’s “in a direct appeal to race hatred” (Reddick 9), was not released until late 1924 because its producer Thomas Ince insisted on waiting until the initial adverse criticism of The Birth of a Nation had simmered down.

The two films, in fact, portrayed similar characters: like the Northern Senator Stoneman, the liberal Northern Judge Lowell in Free and Equal bets that Blacks are equal to whites. But after Alexander Marshall (played, in blackface, by white actor Jack Richardson) hotly pursues Lowell’s daughter, rapes and strangles the family’s maid, and reveals at his trial that he has wed the Judge’s daughter (even though he is already married to a Black woman), the embittered and disillusioned Lowell tears up the lengthy treatise he had been writing in favor of intermarriage, since “the ‘perfect’ Negro” has been exposed as “the perfect rogue” (Bogle, TCMMB 25).

With exceptions such as the African jungle movies and the quasi-historical Southern film So Red the Rose (1935)—based on a novel by Stark Young, in which old Cato (played by Clarence Muse, in a departure from his usual role as the faithful Tom or benign servant) leads his fellow slaves in a short-lived rebellion that is quelled by their young mistress (Margaret Sullavan)—it would be more than half a century before overtly aggressive or sexually assertive Blacks regularly made their way back to the screen. As Donald Bogle and other film historians have demonstrated, it took the success of Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) to signal that the times had changed sufficiently for audiences to accept a radicalized and sexualized Black. The screen was then bombarded with an array of heroes descended from the buck in films such as Shaft (1971), Superfly (1972), Slaughter (1972), and Melinda (1972). [27] And those films, in turn, opened up an entirely new genre of Black action pictures (and arguably a new “type” of Black action hero as well).

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACIAL STEREOTYPES

>>How have recent events such as the murders of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery solidified or challenged some of these longstanding race-based stereotypes and altered racial perceptions?<<

The Mulatto Stereotype

Another unfortunate stereotype that Griffith popularized was the half-Black, half-white mulatto, whom he portrayed as malicious, duplicitous, and conniving and whose only concern was to better his or her status. Mulattoes’ attempts to assimilate and to insinuate themselves into a culture that was not properly their own, moreover, posed a threat to the social order, challenged the racist exclusions of white society, and played into white fears of “mongrelization” of the races. The very presence of such “half-breeds” also raised the ugly specter of interraciality, especially interracial sexuality—although ironically, as Jane Gaines and others have shown, the very mulatto class that white filmmakers sought to discredit was the vestige of slavery days and “the product of the indiscretion of the men of the planter class” (FD 188).

Mulatto characters had already appeared in quite a few earlier short films, in which their racial taint contributed directly to their treachery and served as the basis for some misfortune or tragic event. But Griffith employed the stereotype, as later white filmmakers did, to titillate and evoke horror. In The Birth of a Nation, Griffith had vilified both Silas Lynch, the mulatto leader of renegade Blacks and defiler of white women, and Lydia Brown, Senator Stoneman’s mulatta mistress, who blinded him to the evil ends for which some Blacks were using him. [28] Those character types, like the other racist representations and caricatures, ensured that the film elicited an intense and passionate reaction.

Response by Black Filmmakers

Some, including Black and white activists and prominent Black educators, attempted to respond directly to Griffith’s racist sanctimony. An early film attempt, The Birth of a Race, initiated in 1915 by Emmett J. Scott, personal secretary to Tuskegee Institute President Booker T. Washington, was certainly well-intentioned; but over the next few years, the project passed through many hands; its story was radically altered, and the history it purported to tell was wildly distorted. Finally released in 1918, it proved to be a complete flop.

It was, however, the “race filmmakers” such as George and Noble Johnson (founders of the distinguished Lincoln Motion Picture Company), Oscar Micheaux (founder of the Micheaux Film Company), and Richard E. Norman (founder of the Norman Studios in Arlington, Florida), whose pictures offered the strongest, and most effective, challenge. Determined to counter the prevalent negative images of African Americans on film, those remarkable filmmakers struggled to produce films that (in George Johnson’s words) “display[ed] the Negro as he is in his every day life, a human being, with human inclinations.” And indeed, the Johnson Brothers’ first film, The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition, did just that, thereby setting the standard for future race productions.

The Johnson Brothers’ Lincoln Motion Picture Company film, The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition (1916), was a high-class story of race uplift. Starring Noble Johnson, it set the standard for independent race movies. (Courtesy of the Black Film Center/Archive, Indiana University.)Actor and producer Noble Johnson (1881-1978)A Horatio Alger-story about an engineering graduate of Tuskegee Institute who travels West to find success, it celebrated race uplift and ambition and portrayed the ways that an aspiring Black could overcome barriers and attain all of his ambitions, as James does when he returns to his father’s farm, strikes oil, and marries his beloved Mary.

Micheaux’s Countering of the Stereotypes

Oscar Micheaux, the best-known and most prolific of the early race filmmakers, responded even more directly to Griffith’s race bigotry. In his pictures Within Our Gates (1920) and The Symbol of the Unconquered (subtitled “A Story of the Ku Klux Klan” [1920]), he attempted to reverse many of the familiar racial stereotypes.

Within Our Gates, for instance, graphically portrayed the evils of white vigilante “justice” through the lynching of an innocent, hard-working Black family and depicted a shocking assault by a white man who tries to force himself sexually on a young Black woman who turns out to be his daughter. The violence and the attempted rape served as a stunning counterpoint to Griffith’s distorted depictions of Black lust and brutality.

The career of Oscar Micheaux spanned from 1919 to 1949, during which time he produced more than forty feature films. (Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division.)Graphic scenes of the lynching of a hardworking black couple and the attempted rape of a young Black woman in Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1920). (Courtesy of the Black Film Center/Archive, Indiana University.)The New Genre of Race Films

Still other filmmakers—including the Colored Players Film Corporation of Philadelphia, whose The Scar of Shame (1925) remains one of the finest films, Black or white, of the era, and Richard E. Norman, whose The Flying Ace (1926) offered viewers a military hero they could emulate and aspire to be—attempted to provide more realistic imagery and themes.

Florida-born white filmmaker Richard E. Norman gave his audience strong Black characters such as ace military pilot Captain Stokes (played by Lawrence Criner) in The Flying Ace (1926). (Courtesy of the Norman Studios, Jacksonville, Florida.)While these and other race films did not halt the negative depictions of Blacks in dominant cinema, they typically offered positive portrayals of Black family life and Black ambition, which Black moviegoers welcomed. And that, in turn, helped to give rise to more “Negro-themed” Hollywood movies, beginning with The Jazz Singer (1927) and Hearts in Dixie and Hallelujah (both 1929), productions that did not avoid all—or even many—of the familiar racial cliches but at least recognized the significance of the Black audience that had been long overlooked by white filmmakers.

Conclusion

Yet even today, The Birth of a Nation remains one of the most technically sophisticated and influential films ever produced. The character types that Griffith popularized and that, unfortunately, continue to resonate with some moviegoers today, confirm the powerful impact of The Birth of a Nation and its indisputable role in the birth of defamation of Blacks in American cinema and culture.

PROGRAM LECTURER

Dr. Barbara Tepa Lupack

Dr. Barbara Tepa Lupack, former professor of English and academic dean at SUNY, was Fulbright Professor of American Literature both in Poland and in France. From 2015-2108, she served as New York State Public Scholar. She was also the Helm Fellow at Indiana University (2013), the Lehman Fellow at the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies (2014), and the Senior Fellow at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA (2017-2018). She is author or editor of more than twenty-five books, including Literary Adaptations in Black American Cinema: From Micheaux to Morrison (University of Rochester Press, 2002; expanded ed., 2010), Richard E. Norman and Race Filmmaking (Indiana University Press, 2013), Early Race Filmmaking in America (Routledge, 2016), Silent Serial Sensations: The Wharton Brothers and The Magic of Early Cinema (Cornell University Press, 2020), and Being There in the Age of Trump (Rowman & Littlefield/Lexington Books, 2020).

The Finger Lakes Film Trail program series Making Noise About Silent Film: Conversations About Cinema, Culture, and Social Change is made possible by an Action Grant from Humanities New York, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Humanities New York has been a valued financial supporter of the Finger Lakes Film Trail since its inception in 2018.