Making Noise About Silent Film Series Lecture #2

From Silents to Talking Pictures

by Jim Loperfido

Delivered Wednesday, April 27, 2022, at the Carriage House Theater, Cayuga Museum of History and Art, Auburn, NY

The second lecture in the Making Noise About Silent Film: Conversations about Cinema, Culture & Social Change Lecture Series explores the transition from silent films to talking pictures. Although music was a natural accompaniment to silent films, few early movie studios thought talking pictures had a chance. Jim Loperfido, a film historian who has worked in the industry for more than forty years, discusses how two rags-to-riches moguls—William Fox of Fox Film Corporation, working with Auburn physicist Ted Case, and Sam Warner of Warner Brothers Studio, collaborating with Western Electric—brought the world a new way to experience motion pictures, one that profoundly transformed popular culture.

Silent Motion Pictures

New York City’s Roxy Theatre ran an ad in the New York Times to announce its grand opening in March 1927. Billing itself as “the Cathedral of the Motion Picture” and the “world’s largest theatre,” the Roxy opened with a showing of Gloria Swanson starring in the silent film, The Love of Sunya. (© SZ Photo, Scherl, Bridgeman Images)

By the end of the 19th century, the telephone and radio had made communication easier. Listening to a phonograph and using a camera had become new pastimes, as did viewing the new, impossible-to-resist moving picture shows, which brought the world a new way to experience storytelling entertainment.

Through the first decades of the 1900s, silent films provided cheap entertainment that, unlike stage productions, overcame the language barrier for the millions of immigrants arriving in the United States in the early 20th century. The lack of spoken dialogue was thus an attraction for many audience members.

By the late 1920s, “silent films—an art impassioned by music, focused by darkness, pure emotion transmitted through light—were at the height of their aesthetic and commercial success,” summed up author Scott Eyman in The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution, 1926-1930. But this decade also witnessed technological advances and business stratagems that laid the groundwork for the wildly popular talking pictures that would soon end the silent film heyday.

The Roundhay Garden Scene, filmed by French inventor Louis Le Prince in Leeds, England, on November 16, 1888, is considered the first home movie ever filmed.

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT MASS MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT

>>What is it about visual storytelling that is compelling to audiences?<<

Early Sound Technologies

Edison’s first movie machine, 1886. (Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images)Attempts to link sound to motion pictures go as far back as the 1890s.

Inventor Thomas A. Edison, tired of the hounding by his lab assistant/photographer William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, notified the U.S. Patent Office in 1888 that he was working on a motion picture invention, describing it as “an instrument which does for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear.”

Edison was trying to create a new audiovisual medium that combined music, motion photography, and projected-picture entertainment. “Thus, if one wished to hear and see the concert or the opera, it would only be necessary to sit down at home, look upon a screen and see the performance, reproduced exactly in every movement and at the same time,” Edison told a reporter in 1895. “The voices of the players and singers, the music of the orchestra, the various sounds that accompany a performance of this sort, will be reproduced exactly. The end attained is a perfect illusion.”

In 1895 Edison introduced the Kinetophone, which married the silent Kinetoscope with Edison’s phonograph technology. The Kinetophone did not synchronize sound and image; it merely supplied a musical accompaniment to silent “peep shows.” Edison's crude novelty met with public indifference.

“Blacksmith Scene,” filmed on May 1, 1893 by W.K.L. Dickson for Edison, was the first Kinetoscope film shown in public exhibition and may be the first acting performance filmed.

Dickson’s experimental film test with sound, shot in 1894.

Leon Gaumont’s Chronophone. (“Le Chronophone Gaumont Cinema,” Bridgeman Images)Yet, at the same time, other inventors attempted to improve upon Edison's effort. One of these, Leon Gaumont, demonstrated his Chronophone before the French Photographic Society in 1902. Gaumont's system linked a single projector to two phonographs by means of a series of cables. A dial adjustment synchronized the phonograph and motion picture. To profit by his system, entertainer Gaumont filmed variety, or vaudeville, acts.

Gaumont and Edison did not represent the only phonograph sound systems on the market. More than a dozen others, all introduced between 1909 and 1913, shared common systems and problems.

The Chronophone’s and Kinetophone’s only major rival was the Cameraphone, the invention of E.E. Norton, a former mechanical engineer with the American Gramophone Company. One of the more interesting aspects of the Cameraphone technology was the method of amplification, though its amplification could not reach all patrons in a large hall. Even though in design the Cameraphone replicated Gaumont's apparatus, Norton succeeded in installing his system in a handful of theaters.

Like others who preceded him, Norton never solved fundamental problems: the apparatus was expensive, and maintaining synchronization for lengthy periods of time proved impossible. In addition, since the Cameraphone system required a porous screen, the projected images appeared gray and dingy. Therefore, it was not surprising that Cameraphone (or the similar Cinephone, Vivaphone, and Synchroscope) was never successful.

Edison’s Kinetophone

Wills’s Cigarettes printed a series of cigarette cards illustrating “Famous Inventions,” including this image of a projectionist using a modified kinetoscope to project moving pictures with sound. (Private Collection, © Look and Learn, Bridgeman Images)In 1913, Edison announced a revamped Kinetophone. This time, the Menlo Park inventor argued, he had perfected the talking motion picture! Edison's demonstration on January 4, 1913, impressed all present. The press noted that this system seemed more advanced than all its predecessors. Its sensitive microphone did away with lip-sync difficulties for actors, and an oversized phonograph supplied maximum mechanical amplification. An intricate system of belts and pulleys erected between the projection booth and the stage was intended to precisely coordinate the speed of the phonograph with the motion picture projector.

The Photo-Drama of Creation (1914), a four-part, eight-hour Jehovah’s Witnesses’ film, synchronized live action and slides with music and lectures on phonograph discs. This was the first major film using the Kinetophone. Over nine million people in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand saw it. (Wikimedia Commons)Because of the success of the demonstration, Edison was able to persuade vaudeville magnates John J. Murdock and Martin Beck to install the Kinetophone in four Keith-Orpheum theaters in New York. The commercial premiere of Edison’s Kinetophone took place on February 13, 1913, at Keith's Colonial. A curious audience first viewed and listened to a lecturer who praised Edison's latest marvel. To provide dramatic evidence for his glowing tribute, the lecturer then smashed a plate, played the violin, and had his dog bark.

After several musical acts (recorded on the Kinetophone), a choral rendition of "The Star- Spangled Banner" stirringly closed the show. An enthusiastic audience stood and applauded for ten minutes. The wizard, Tom Edison, had done it again!

Unfortunately, this initial performance would rank as the zenith for Kinetophone. For most later presentations, the system functioned poorly. Keith's Union Square theatre experienced sound synchronization issues, with sound lagging film by as much as ten to twelve seconds. The audience booed one picture off the screen.

By 1914, the Kinetophone had lost its shine due to its inconsistent performance. Murdock and Beck canceled their contract with Edison. Edison's West Orange factory was destroyed by fire that same year. Edison chose to scrap the Kinetophone soon after. The West Orange fire not only marked the end of the Kinetophone but signaled the demise of all serious efforts to unite the phonograph with the motion picture projector.

Jack’s Joke (1913), made by Edison using the Kinetophone.

American moviegoers had to wait nine years for a workable, easy-to-use sound system to emerge. When it did, it was based on the principle of sound on film, not on phonograph discs.

Tom Edison, The Father of U.S. Cinema

Interview with Thomas Edison on his 84th birthday in 1931

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT MASS MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT

>>Was music a must-have accompaniment to silent film?<<

Western Electric’s Sound Work

It took American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T), in the running for the world's largest company at the time, to succeed where others had failed. In 1912, AT&T's manufacturing subsidiary, Western Electric, secured the rights to American electrical engineer Lee de Forest's Audion vacuum tube to build amplification repeaters for long-distance telephone transmission. They then set their sights on sound amplification. Within three months of the World War I armistice in 1918, another essential element for a sound system was ready: the loudspeaker.

First used in the Victory Day parade on Park Avenue in 1919, the loudspeaker drew increased attention during the 1920 Republican and Democratic national conventions. A year later, by connecting this technology to its long-distance telephone network, AT&T broadcast President Warren G. Harding’s address at the burial of the Unknown Soldier simultaneously to overflowing crowds in New York's Madison Square Garden and San Francisco's Convention Center. Clear sound transmissions to large indoor audiences had become a reality.

Lee de Forest displays two types of Audion vacuum tubes, ca. 1919. (James H. Collins, "The genius who put the jinn in the radio bottle," Popular Science, Vol. 1, No. 1, May 1922, p. 31. Wikipedia)President Harding had a keen interest in technology. On June 14, 1922, the speech that Harding delivered in Washington, D.C., at the dedication of the Francis Scott Key Memorial was broadcast over the radio. This was the very first time the voice of an American president was broadcast to the public via the radio. (Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images)Western Electric Links Sound to Moving Images

“The Spirit of Communication” Western Electric Logo, 1914. (Wikipedia)In 1922, Western Electric began to consider novel commercial applications for its sound technology. They were already advertising and selling microphones, vacuum tubes, and loudspeakers in the radio field, but they soon realized that more lucrative markets existed in "improved" phonographs and sound movies.

Employing the sound-on-disc method, they produced The Audion, the first motion picture using Western Electric's sound system. Made at Western Electric's plant in Chicago, the film featured a soundtrack recorded on a phonograph disc and synchronized to a projected moving picture. Other necessary film exhibition components quickly flowed off Western Electric's research assembly line. The complete disc system included a suite of high-tech parts: a high-quality microphone, a distortion-free amplifier, an electrically operated recorder and turntable, a high-quality loudspeaker, and a synchronizing system free from speed variation. By the fall of 1924, the sound-on-disc system seemed ready to market.

Laboratory success did not constitute the only criterion that distinguished Western Electric's efforts from those of other inventors. Most importantly, Western Electric had almost unlimited financial muscle. In 1925, parent company AT&T ranked with U.S. Steel as the largest private corporation in the world. Western Electric, although technically an AT&T subsidiary, ranked as a corporate giant itself, with assets of $188 million and sales of $263 million, far more than even Paramount, the largest force in the motion picture industry at the time.

Using its financial power and patent position, Western Electric moved to reap large rewards from its sound recording technology. As early as 1925 it had aroused enough interest to license the key phonograph and record manufacturers, Victor and Columbia. Movie executives proved more stubborn.

Competition for the Next Sound Innovation

An early Warner Brothers Studio building in Burbank, California, ca. 1920s. (Bridgeman Images)By 1926 competition for the next great film revolution was at its peak. Many small inventor-entrepreneurs attempted to marry motion pictures and sound, but it took two corporate giants, AT&T and the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), to develop the necessary technology.

AT&T desired to make better phone equipment; RCA sought to improve its radio capabilities. As a secondary effect of their research, each perfected sound recording and reproduction equipment. With the technology ready, two movie companies, Warner Brothers and Fox, were the first to adapt telephone and radio research for practical use. That is, they revolutionized sound film.

The speed of conversion surprised everyone: within two years, many technical problems were overcome, stages soundproofed, and theaters wired. Engineers invaded studios to coordinate sight with sound. Playwrights (from the East Coast) replaced title writers; actors without stage experience rushed to sign up for voice lessons. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Warner Brothers Pictures needed something exciting, and one brother thought sound might be it. According to film critic Edward Kellogg and others, Warner Brothers in particular, desperately wanting to break into the higher echelons of Hollywood power, committed themselves to the adoption of sound motion pictures in 1926. However, just a year earlier, in 1925, Warner’s ranked low in the economic pecking order in the American film industry. Brothers Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack had come a long way since their days as nickelodeon operators in Ohio some two decades earlier. Yet, in the mid-1920s, their future seemed severely constrained.

Warners neither controlled an international system for distribution nor owned a large chain of first-run theaters. The brothers' most formidable rivals, Famous Players (soon to be renamed Paramount), Loew's, and First National, did.

Warner Bros. Prepares for Sound

Movie producer Harry Rapf, at left, meets with the four Warner brothers, from left: Sam Warner, Harry Warner, Jack Warner, and Abraham “Albert” Warner. (Bridgeman Images)Eldest brother Harry Warner, a shrewd and patient man, remained optimistic about sound and movies and sought help. He turned to Waddill Catchings, a financier with Wall Street's Goldman Sachs. Catchings had a reputation as the boldest of the "New Era" Wall Street investors. He agreed to work with Warner, believing that the consumer-driven 1920s economy would provide a fertile ground for limitless growth in the movie industry. Catchings agreed to finance Warner’s only if they followed his overall plan. The four brothers, sensing they would find no better alternative, agreed.

Overnight Warner Brothers had acquired a permanent source for financing future productions. Warners quickly took over the struggling Vitagraph Corporation, complete with its network of fifty distribution exchanges throughout the world. In this deal, Warner’s also gained the pioneer company's two small studios, processing laboratory, and extensive film library. Finally, with another $4 million that Catchings raised through bonds, Warner Brothers strengthened its distribution system, even launching its own ten-theater chain. It began by acquiring the Stanley Company, which owned a chain of three hundred theaters along the East Coast, and First National Studios. By mid-1925, Warner’s was becoming a force to be reckoned with in the American movie business.

This expansion plan set the stage for the possible coming of sound. At the urging of Sam Warner, who was an electronics enthusiast, the company established radio station KFWB in Hollywood to promote Warner Bros. films. The equipment was secured from Western Electric. Until then, there were no takers for Western Electric's sound inventions. Past failures had made a lasting and negative impression on the industry leaders, a belief strongly shared by Harry Warner.

Vitaphone is Born

Sam Warner was 37 years old and a magnet for anything high tech when Western Electric’s Nathan Levinson invited him to experience a sound system. Sam accepted like a “spring Lamb seeing an open field,” says film author Michael Freedland. Sam called it “the most exciting thing I have ever seen” and could not wait to tell his brothers. He knew Harry, the lead Warner, and Abe, the Warner treasurer, had to be tricked into attending a demonstration.

That screening, in May 1925, included a recording of a five-piece jazz band. Harry and other Warner Brothers executives loved it and reasoned that if Warner Brothers could equip its newly acquired theaters with sound and present vaudeville acts as part of their programs, it could successfully challenge the Big Three. Then, even Warner’s smallest house could offer famous vaudeville acts on film as silent features with the finest orchestral accompaniments recorded on disc. Warners, at this point, never considered feature-length talking pictures, only singing and musical films.

All of the General Electric advanced components came together in the Vitaphone sound movie film projector, shown here in 1926, with Western Electric engineer E.B. Craft on the left. (Unnamed photographer for Vitaphone/AT&T, History Department at the University of San Diego, Wikipedia)Catchings endorsed such reasoning and gave permission to open negotiations with General Electric. On June 25, 1925, Warner Brothers signed a letter of agreement with Western Electric calling for a period of joint experimentation. Western Electric would supply the engineers and sound equipment, Warner Brothers the camera operators, the editors, and the supervisory talent of Sam Warner. Work commenced in September 1925 at the old Vitagraph studio in Brooklyn to produce the Vitaphone sound system.

Meanwhile, Warner Brothers continued to expand under Waddill Catching's careful guidance. Although feature film output was reduced, more money was spent on each picture. In the spring of 1926, Warner Brothers opened a second radio station and an additional film processing laboratory, and further expanded its foreign operations. Given these intense capital investments, the firm expected the $1 million loss on its annual income statement issued in March 1926.

Vitagraph unveiled its Vitaphone marvel on August 6, 1926, at the Warner Theater in New York. The first-nighters who packed the house paid up to $10 for tickets. The program began with eight "Vitaphone Preludes." In the first spot, Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America President Will Hays congratulated the brothers Warner and Western Electric for their pioneering efforts. Next, conductor Henry Hadley led the New York Philharmonic in the overture to Tannhäuser. Soprano Anna Case sang, supported by the Metropolitan Opera Chorus. The silent feature Don Juan followed a brief intermission. The musical accompaniment (sound-on-disc) caused no great stir because it "simply replaced" an absent live orchestra.

That autumn, thanks to Sam Warner, who insisted it be made with a Vitaphone soundtrack, the Don Juan package played in Atlantic City, Chicago, and St. Louis. Quickly, Vitaphone organized a second program, but this time aimed for the rank-and-file moviegoer.

Warner Brothers released Don Juan in 1926. The adventure-plus-romance film became the first full-length release using the Vitaphone sound system. The feature film had no spoken dialogue, but it included a synchronized musical score and sound effects. (Wikipedia)Scene from Don Juan (1926). Don Juan, played by John Barrymore, has met his match in the powerful Lucrezia Borgia, played by Estelle Taylor. Barrymore’s portrayal of Don Juan, one of fiction’s legendary lovers, is mesmerizing. (Auburn Cinefile Society)The feature “Don Juan,” starring John Barrymore, Mary Astor, and Estelle Taylor, was released on August 6, 1926. Available from Warner Brothers Archive Collection.

As a result of the growing popularity of Vitaphone presentations, the company succeeded in installing a hundred systems by the end of 1926. Most of these were in the East. The installation in March 1927 of apparatus in New York City’s new Roxy Theater and the publicity garnered served to spur business even more. Finally, the financial health of Warner Brothers showed signs of improvement.

The Switch to Talkies

The Jazz Singer (1927), the first American-made, feature-length motion picture with a synchronized music score, singing, and some speech, is considered a part-talkie today. This film was pivotal for Warner Brothers in using the sound-on-disc system to bring the studio success and attention. Its acceptance was a death knell for silent films. (Wikipedia)As the 1927-1928 theatrical season opened, and again thanks to Sam’s insistence, Vitaphone began to add new forms of sound films to its program. Though The Jazz Singer premiered on October 6, 1927, to lukewarm reviews, its four Vitaphone segments of Al Jolson's songs proved extremely popular. Vitaphone contracted with Jolson immediately to make three more films for $100,000. The four Warner brothers did not attend The Jazz Singer's New York premiere because Sam Warner died in Los Angeles on October 5. Jack Warner took over as head of Vitaphone production.

During Christmas week 1927, Vitaphone released a 20-minute, all-talking drama, Solomon's Children. Again, revenues were high, and in January 1928 they moved to schedule production of two all-talking shorts per week. Harry Warner and Waddill Catchings knew the investment in sound was a success by April 1928.

By then it had become clear that the Warner-produced Jazz Singer had become the most popular entertainment offering of the 1927-1928 season. In cities that rarely held films for more than one week, The Jazz Singer and its accompanying shorts set records for length of run: for example, five-week runs in Charlotte, North Carolina; Reading, Pennsylvania; Seattle, Washington; and Baltimore, Maryland. By mid-February 1928, The Jazz Singer package was in a record eighth week in Columbus, Ohio; St. Louis, Missouri; and Detroit, Michigan; and a record seventh week in Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon; and Los Angeles, California. The Roxy even booked The Jazz Singer bill for an unprecedented second run in April 1928, where it grossed more than $100,000 each week, among that theater's best grosses of the season.

Crucially, these first-run showings did not demand the usual expenses for a stage show and orchestra.

“The Jazz Singer,” starring Al Jolson, May McAvoy, Warner Oland, and Eugenie Besserer, was released on October 10, 1927. Available from Warner Brothers Archive Collection.

It took Warner Brothers only until the fall of 1928 to convert to the complete production of talkies—both features and shorts. Catchings and Harry Warner had laid the foundation for this maximum exploitation of profit with their slow, steady expansion in production and distribution. In 1929 Warner Brothers would become the most profitable American motion picture company.

Part-Talkies

A part-talkie is a partly, and most often primarily, silent film which includes one or more synchronous sound sequences with audible dialogue or singing. During the silent portions, lines of dialogue are presented as "titles"—printed text briefly filling the screen—and the soundtrack is used only to supply musical accompaniment and sound effects.

In the case of feature films made in the United States, nearly all such hybrid films date to the 1927-1929 period of transition from "silents" to full-fledged "talkies," with audible dialogue throughout. It took about a year and a half for a transition period for American movie houses to move from almost all silent to almost all equipped for sound. In the interim period, studios reacted by improvising four solutions: fast remakes of recent productions, "goat gland" pictures with one or two sound sequences spliced into already finished productions, dual sound and silent versions produced simultaneously, and part-talkies.

The so-called first talking picture, The Jazz Singer (1927), starring Al Jolson, is in fact a part-talkie. It features only about fifteen minutes of singing and talking, interspersed throughout the film, while the rest is a typical silent film with titles and only a recorded orchestral accompaniment.

Lobby card from The Jazz Singer (1927). Directed by Alan Crosland, this part-talkie features six songs performed by Al Jolson and a few scenes with spoken dialogue. Based on the 1925 play of the same title by Samson Raphaelson, the plot was adapted from his short story, "The Day of Atonement." (Wikipedia)

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT MASS MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT

>>Since silent films required active engagement by the audience to interpret the storytelling on the screen, did the introduction of sound take away that component of audience response to filmed entertainment?<<

The Technological Contributions of de Forest and Case

Lee de Forest began to work on a practical system for recording and reproducing sound motion pictures. (Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images)Theodore Case possibly filming family with camera on tripod. (Case Research Laboratory, Cayuga Museum of History and Art)At the same time that the Warners and Western Electric were joining forces to advance film sound technology, a parallel but technologically distinct effort was underway. Initially touched off by the work of two independent inventors, electronics whiz Lee de Forest and Auburn scientist Theodore “Ted” Case, a new sound-on-film technology would be developed and adopted first by minor player Fox Film Studio.

In 1907, Lee de Forest had patented the Audion amplifier tube and used it in his Phonofilm system that he later described as photographing the voice directly onto film stock. In that same year he premiered the Phonofilm at New York's Rivoli Theatre. The program consisted of three shorts: a ballet dancer performing a "swan dance," a string quartet, and another dance number. The showing generated little interest. A New York Times reporter described a lukewarm audience response. None of the movie moguls saw enough of an advancement, given repeated previous failures of other sound innovations, to express more than a mild curiosity.

In 1913, the independently wealthy, Yale-trained physicist Ted Case established a private laboratory in his Auburn, New York, hometown. Spurred by recent breakthroughs in the telephone and radio fields, Case and his assistant Earl I. Sponable sought to improve the Audion tube. In 1917, they perfected the Thalofide Cell, a highly improved light-sensitive vacuum tube, and began to integrate this invention into a system for recording sounds. As part of this work, Case met Lee de Forest.

The Case Research Laboratory (CRL) invented the AEO light, a very sensitive cell (light bulb) that could react to variations in sound waves. Two years later the CRL began working on its own sound film system, recording test films in the carriage house behind Theodore Case’s mansion. (Case Research Laboratory, Cayuga Museum of History and Art)De Forest first reached out to Case about whether he had considered using the Thalofide Cell to make sound film in 1920. According to letters in the Case Research Lab records, de Forest overwhelmingly agreed that Case’s invention was a significant improvement over all others. De Forest was most interested in whether Case would make special orders of Thalofide Cells for his use. A working relationship was established between de Forest and Case that would irritate the Auburn inventor throughout its existence. On April 4, 1923, de Forest, having incorporated technological contributions from Case to improve his sound-on-film process, successfully exhibited the Phonofilm system to the New York Electrical Society.

This 1923 presentation represented the peak of de Forest’s Phonofilm success. Legal and financial roadblocks continuously hindered any considerable progress. Due to myriad issues, Ted Case walked away from the loosely formed partnership. De Forest tried but could not establish anywhere near an adequate organization to market films or the apparatus.

According to film critic Scott Eyman, movie entrepreneurs feared that the Phonofilm Corporation controlled too few patents ever to succeed in the litigious world of film production. Many considered de Forest a brilliant individualist who failed to master the intricacies of the world of modern finance. Between 1923 and 1925, Phonofilm, Inc. wired only thirty-four theaters in the United States, Europe, South Africa, Australia, and Japan. De Forest struggled on, but in September 1928, when he sold out to a group of South African businesspeople, only three Phonofilm installations remained, all in the United States.

“Bard/Pearl Vaudeville,” Lee de Forest’s 1923 film made with his Phonofilm System

Ted Case’s 1925 test films

Case’s test film of prison reformer Thomas Mott Osborne

Case Partners with Fox Film

William Fox Studio at the corner of Western and Fernwood avenues in Hollywood, California, circa 1923. (Auburn Cinefile Collection)For business and personal reasons, Case turned all of his laboratory's efforts to besting de Forest. Within eighteen months, Case Labs had produced an improved sound-on-film system, again based on the Thalofide Cell. Case quietly constructed, with his own funds, a complete sound studio and projection room adjacent to his Auburn laboratory.

In 1925, Case determined that he was ready to market his inventions. Sponable invited Edward Craft of Western Electric to Auburn, hoping to use their sound-amplification system for commercial sound films. Craft saw (and heard) a demonstration film and left quite impressed. He later sent two Bell Telephone experts to Auburn, and the seconded his positive assessment. However, after careful consideration, Western Electric decided that Case's patents added no substantial improvement to the sound-on-disc system they had developed, then under exclusive contract to Warner Brothers.

Rebuffed, Case decided to solicit a show business entrepreneur directly. He first approached John J. Murdock, the long-time general manager of the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit. Case argued that his sound system could be used to record musical and comedy acts--the same idea Harry Warner had conceived of six months earlier. Murdock had been burned by Edison a decade earlier, just as he had been more recently by de Forest. Keith-Albee would never be interested in talking movies, he answered! Executives from all the "Big Three'' motion picture corporations, Paramount, Loew's (MGM), and First National, echoed Murdock's response. None saw the slightest benefit in this latest version of sight and sound. Case moved to the second tier of the U.S. film industry: Producers Distributing Company (PDC), Film Booking Office (FBO), Warner Brothers, Universal, and Fox.

William Fox (Wikipedia)Sponable contacted John Joy, an old Cornell friend who represented Courtland Smith, president of Fox Newsreels, arguing that using sound-on-film technology to produce newsreels could push that branch of Fox Film to the forefront of the industry. In June 1926, Smith asked Case to arrange a New York demonstration for company owner, founder, and president William Fox. Both Case and Sponable demonstrated their sound system to Fox representatives at the Fox Nemo Theater’s Parlor B on 10th Avenue, followed by a decisive private screening at William Fox’s home in Woodmere, New York.

Fox was arguably the most dynamic, entrepreneurial, and finicky of the movie moguls at the time. He sensed a possible—and profitable—disruption of the old system of film presentation. Smith knew that if Fox liked what he saw, nothing would stop him from claiming it for his own company and being the first adopter of a dramatic technological shift.

William Fox judged Case and Sponable’ s system a potentially vast improvement over the cumbersome Western Electric disc system. In July 1926, William Fox formed the Fox-Case Corporation to license the Case Laboratory developments to reinvent his Movietone News Service that had been set up in 1910. Case turned all patents over to the new corporation. Fox Films controlled 25 percent of the new company, and the remaining 75 percent was divided among Fox Theaters, William Fox, and Theodore Case and associates. Fox-Case assumed all liability regarding any lawsuits. Case received 2,500 shares of Fox preferred stock and 25,000 shares of common stock, and he was hired as a consultant to the new corporation. The Case Research Lab was contracted to manufacture Thalofide Cells for the next three years. Sponable joined the new company. In December 1926, Fox also bought the rights to use Western Electric’s amplifiers.

Earl Sponable at Fox Studios in New York City (Case Research Laboratory, Cayuga Museum of History and Art)Fox Film Studio’s Expansion Plan

Initially, William Fox's approval of experiments with the Case technology constituted only a small portion of a comprehensive plan to thrust Fox Film into a preeminent position in the motion picture industry. Fox and his advisers had initiated an expansion campaign in 1925. By floating $6 million of common stock, they increased budgets for feature films and enlarged the newsreel division. (Courtland Smith was hired at this point.)

Simultaneously, Fox began building a chain of motion picture theaters. At that time Fox Film controlled only twenty small neighborhood houses in the New York City environs. By 1927 the Fox chain included houses in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Brooklyn, New York City, St. Louis, Detroit, Newark, Milwaukee, and a score of cities west of the Rockies.

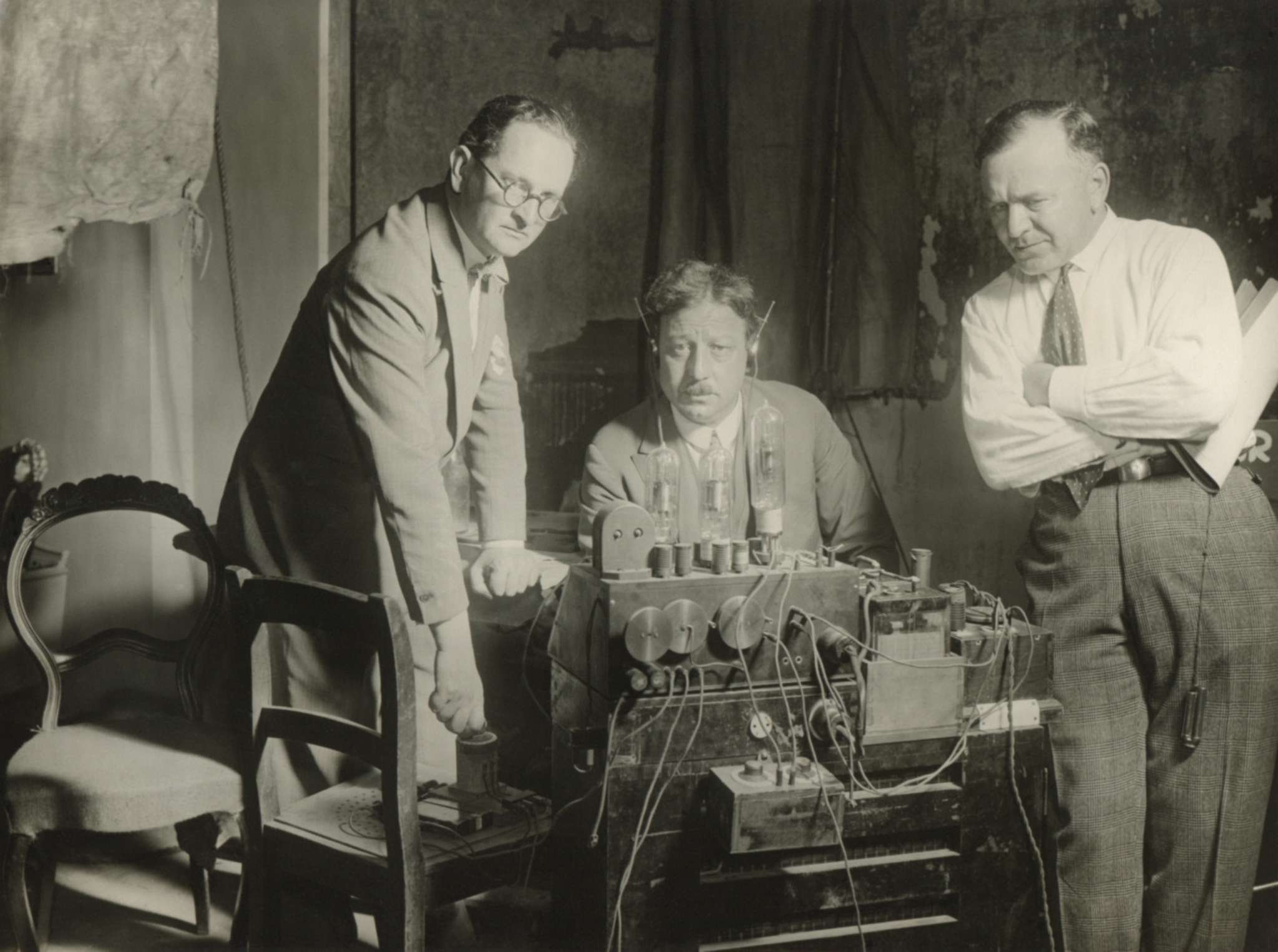

In 1919, German inventors Josef Engl (shown at left), Hans Vogt (at right), and Joseph Massolle (center) patented the Tri-Ergon system. The trio gave a public screening of a sound movie using the system on September 17, 1922. Tri-Ergon became Europe’s dominant sound-on-film system. (Everett Collection, Bridgeman Images)Meanwhile, Courtland Smith had assumed control of Fox-Case, and, in 1926, initiated the innovation of the Case sound-on-film technology. At first all he could oversee were defensive actions designed to protect Fox-Case's patent position. In September 1926, exactly two months after incorporation, Fox-Case successfully thwarted claims by Lee de Forest and Tri-Ergon. Fox-Case advanced $50,000 to Tri-Ergon to check the potential of future court action. At last Fox-Case could assault the marketplace.

Although Smith pushed for immediate experimentation with sound newsreels, William Fox conservatively ordered Fox-Case to imitate Warner’s strategy of filming popular vaudeville acts. On February 24, 1927, Fox executives felt confident enough to stage a widely publicized demonstration of the newly christened Movietone system. At 10:00 in the morning, fifty reporters entered the Fox studio near Times Square and were filmed using the miracle of Movietone. Four hours later the press corps saw and heard themselves as part of a private screening.

Fox presented several vaudeville shorts with sound, including a banjo and piano act, a comedy sketch, and three songs by the then-popular cabaret performer Raquel Meller. The strategy worked, and Fox soon ordered sound systems for twenty-six of his largest first-run theaters, including the recently acquired Roxy.

Fox’s Movietone Newsreels

Fox Movietone was everywhere in the world it needed to be, aided by mobile film crews equipped with Movietone film gear. (Case Research Laboratory, Cayuga Museum of History and Art)Smith pressed Fox again to consider newsreels with sound. Sound newsreels would provide a logical method for Fox-Case to perfect the necessary new techniques of camerawork and editing. Convinced, William Fox ordered Smith to make it happen. This decision would prove more successful for Fox Film's overall goal of corporate growth than either William Fox or Courtland Smith imagined at the time.

The sound newsreel premiere came on April 30, 1927, at the Roxy in the form of a four-minute record of marching West Point cadets. Despite the lack of any buildup, this newsreel elicited an enthusiastic response from the trade press and New York-based motion picture reviewers. Quickly Smith seized upon one of the most important symbolic news events of the 1920s—aviator Charles Lindbergh’s history-making solo nonstop transatlantic flight.

At 8:00 A.M. on May 20, 1927, Lindbergh took off in his Spirit of St. Louis monoplane from New York City for Paris. That evening Fox Movietone News presented footage of the takeoff—with sound—to a packed house at the Roxy Theatre. Six thousand persons stood and cheered for ten minutes. The press saluted this new motion picture marvel and noted how it had brought alive the heroics of the "Lone Eagle." In June, when Lindbergh returned to a tumultuous welcome in New York City and Washington, D.C., Movietone News camera operators also recorded portions of those celebrations.

Both William Fox and Courtland Smith were now satisfied that the Fox-Case system had been launched onto a propitious path. Smith and Fox decided again to try to produce vaudeville shorts, as well as silent feature films accompanied by synchronized music on disc. Two earlier silent features, Seventh Heaven and What Price Glory?, were re-released with synchronized musical scores.

In 1927, Fox released German director F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. Murnau was a well-known director in Germany and a leader of the expressionist movement. His masterpieces included Nosferatu and The Last Laugh when he was invited by William Fox to direct a film for his studio. Fox granted Murnau great “financial and artistic freedom” to make a “highly artistic picture.” It received the Academy Award for “Unique and Artistic Picture” during the first year of the Academy Awards (and the first and only time this category existed as distinct from Outstanding Picture). Film historian William K. Everson concluded that the “more substantial stylistic design of Sunrise can stand side-by-side as representing the peak achievements of Hollywood’s designers just before sound took over.” Interestingly, Fox could not have afforded to make Sunrise without its profits from the many Rin Tin Tin movies it churned out.

George O’Brien and Janet Gaynor starred in Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (also known as Sunrise), the 1927 silent romantic drama directed by German director F. W. Murnau (in his American film debut) that also features Margaret Livingston. (Auburn Cinefile Collection)Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927). (IMDb.com)“Sunrise,” starring George O'Brien, Janet Gaynor, and Margaret Livingston, was released on September 23, 1927. Available from 20th Century Fox Studio Classics.

The film was not a success at the box office, however. It was overshadowed by The Jazz Singer, the first talkie, released only two weeks later. Sunrise used the Movietone system with sound recorded optically on the film itself. Sunrise only included music and sound effects, while the Warner Bros.’s Jazz Singer included a couple of spoken dialogues. Sunrise, however, remains one of the high points of silent films, combining American-style storytelling with visual effects mostly seen (until then) in European films. Today it is considered one of the greatest films ever made.

By January 1928 Fox had filmed ten vaudeville shorts and a part-talkie feature, Blossom Time. During the spring of 1928, these efforts, along with Fox's newsreels and Warners’ shorts and part-talkies, proved to be the hits of the season. Thus, in May 1928 William Fox declared that 100 percent of the upcoming production schedule would be Movietone. Simultaneously Fox Film continued to wire, as quickly as possible, all the houses in its ever-expanding chain, and draw up plans for an all-sound Hollywood-based studio. Fox's innovation of sound neared completion; colossal profits loomed on the horizon.

William Fox’s vision and Theodore Case’s tenacity and inventions changed the movie landscape forever. The ripple effect of their collaboration is still evident close to 100 years later.

Finale

The public's infatuation with sound ushered in another boom period for the film industry at a time when the country and the world needed it most. Paramount's profits jumped $7 million between 1928 and 1929, Fox's $3.5 million, and Loew's $3 million. Warner Brothers, however, set the record: its profits increased by $12 million, from a base of only $2 million—a 600 percent leap. Conditions were ripe for consolidation.

Clara Bow experiments with color film. Clara Bow rose to stardom during the silent film era of the 1920s and successfully made the transition to "talkies" in 1929. Her appearance as a spirited shopgirl in the film “It” brought her global fame and the nickname "The It Girl." Bow came to personify the Roaring Twenties.

Warner Brothers, with its early start in sound, had set the pace for this explosive growth. By 1929 all the studios were re-cutting films originally shot as silent to be exhibited in sound. Pathé re-released director Cecil B. DeMille’s “King of Kings” with a synchronized score; it would be a decade before the sound era produced anything remotely comparable. In July 1928, the Exhibitors Herald movie trade paper provided the following line-up of film studios transitioning to sound:

· Western Electric, licensing both film and disc methods;

· Warners, with Vitaphone on disc;

· Fox-Case, Paramount, MGM, United Artists, and Universal with Movietone on film;

· Hal Roach Comedies, presumed Movietone on film;

· Christie Comedies, mostly Movietone on film;

· Columbia Pictures, unknown, though ready to join Western Electric.

By early 1929, Photophone, Phonofilm, Vitaphone, European Tri-Ergon, Cinephone, and Movietone led the field of companies selling a sound process for film. This period, much like the early 1900s when the silent era began, was ushered in with dozens of lawsuits. Everyone was suing everyone else. By 1930 there were some 230 distinct types of theater sound equipment. As a result, exhibitors screamed for uniformity. Nothing was clear, and no one knew who the winner of the sound contest would be. Ultimately, however, the Vitaphone disc process would not make it to the end of the race, and sound-on-film would become the prevailing standard.

Most all praise goes to the winners of the battle. In this film story William Fox and Theodore Case reign supreme. Their tenacity and vision pushed through a system that revolutionized film production and delighted films enthusiasts worldwide.

However, neither Fox nor Case lasted very long in the film industry after their efforts to bring sound-on-film to fruition. William Fox’s contributions are hardly mentioned by the studio that bears his last name today, and you will not find Theodore Case’s name anywhere on Hollywood’s famous Walk of Fame.

Watch the Presentation

PROGRAM LECTURER

Jim Loperfido

A business consultant and film historian, Jim Loperfido is the past Board Chair and CEO of the Syracuse International Film Festival. Loperfido has overseen a number of independent film and video production entities and lobbied on behalf of the entertainment industry in Washington, D.C. He has also written on a number of film topics, including the Wharton Brothers in Ithaca, Carlyle Blackwell, and a compendium of Central New York films.

The Finger Lakes Film Trail program series Making Noise About Silent Film: Conversations About Cinema, Culture, and Social Change is made possible by an Action Grant from Humanities New York, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Humanities New York has been a valued financial supporter of the Finger Lakes Film Trail since its inception in 2018.